By Mariano Castillo and Osmary Hernandez, CNN

March 6, 2013

- Chavez, 58, led a wave of leftist leaders in Latin America

- His idol was Simon Bolivar

- Reforms took socialist path

- Critics said many of his programs were unsustainable

Chavez, who had battled cancer,

was 58.

Chavez's democratic ascent to the

presidency in 1999 ushered in a new era in Venezuelan politics and its

international relations.

Hugo Chavez's

legacy

A look at the life of Hugo

Chavez

Vice president: Hugo Chavez is

dead

Hugo Chavez's 2009 interview

with CNN

Once a foiled coup-plotter, the

swashbuckling former paratrooper was known for lengthy speeches on everything

from the evils of capitalism to the proper way to conserve water while

showering. He was the first of a wave of leftist presidents to come to power in

Latin America in the last dozen years.

As the most vocal U.S. adversary

in the region, he influenced other leaders to take a similar stance.

But the last months of Chavez's

life were marked by an uncharacteristic silence as his health worsened. Chavez

underwent a fourth surgery on December 11 in Cuba, and was not publicly seen

again. A handful of pictures released in February were the last images the

public had of their president.

Chavez's ministers stubbornly

maintained a hopeful message throughout the final weeks, even while admitting

that the recently re-elected president was weakened while battling a respiratory

infection.

President concentrated

country's power

Chavez launched an ambitious

plan to remake Venezuela, a major oil producer, into a socialist state in the

so-called Bolivarian Revolution, which took its name from Chavez's idol, Simon

Bolivar, who won independence for many South American countries in the early

1800s.

"After many readings, debates,

discussions, travels around the world, etcetera, I am convinced -- and I believe

this conviction will be for the rest of my life -- that the path to a new,

better and possible world is not capitalism. The path is socialism," he said on

his weekly television program in 2005.

Chavez redirected much of the

country's vast oil wealth, which increased dramatically during his tenure, to

massive social programs for the country's poor. He expanded the portfolio of the

state-owned oil monopoly to include funding for social "missions" worth millions

of dollars. That helped pay for programs that seek to eradicate illiteracy,

provide affordable food staples and grant access to higher education, among

other things.

But Chavez also leaves a legacy

of repression against politicians and private media who opposed him.

He concentrated power in the

executive branch, turning formerly independent institutions -- such as the

judiciary, the electoral authorities and the military -- into partisan

loyalists.

Photos:

Celebrities and Hugo Chavez

Ban Ki-moon reacts to Chavez's

death

The relationship between

Chavez and U.S.

2006: Chavez calls Bush 'the

devil'

Through decrees and a judiciary

tilted in the president's favor, many political opponents found themselves

barred from running in elections against the ruling party. Even former allies,

like Chavez's onetime defense minister, Gen. Raul Baduel, faced accusations that

critics called trumped-up corruption charges.

Chavez's government similarly

targeted opposition broadcasters, passing laws and decrees that forced at least

one major broadcaster and dozens of smaller radio and television stations off

the air.

Opponents also have criticized

his social programs, calling them unsustainable over the long run and

responsible for unintended consequences. Price controls, for instance, drove up

inflation, while expropriations of farmland depressed production.

Vocal critic of American

policy

In lengthy, freewheeling

speeches, Chavez saved his most acerbic barbs for the "imperialist" United

States and its "colonial" allies in the region.

He accused the United States of

trying to orchestrate his overthrow, and referred to President George W. Bush as

the devil in front of the United Nations General Assembly.

At home, business interests

accused him of scaring off investment by abusing the power of expropriation.

Venezuela struggled to grow its economy during this period, even as the nation

was flush with money from oil, which was at about $17 a barrel when Chavez took

office and rose to more than $100 a barrel.

In addition to domestic social

programs, the Chavez government pumped money into his foreign policy interests.

He invested millions of dollars in oil and cash in countries that were

ideologically similar.

Chavez considered former Cuban

leader Fidel Castro a mentor, and aligned his country with Iran and other

nations opposed to the United States.

Cuba loses a benefactor in

Chavez, whose provision of an oil lifeline at below-market prices could be at

risk under a new government.

While Chavez admired Castro, he

found most inspiration from Bolivar, even renaming the country the Bolivarian

Republic of Venezuela.

An affable, if sometimes

bombastic, man, Chavez had a disarming manner that even his critics could not

deny.

Some called his style

buffoonish, but he spoke like an ordinary Venezuelan -- not like a bureaucrat --

and voters reacted positively.

Other leftist leaders elected

after him, like Bolivia's Evo Morales, Ecuador's Rafael Correa and Nicaragua's

Daniel Ortega, followed Chavez's example to varying extents.

Chavez could also be secretive.

He was slow to publicly admit that he had cancer, and never shared what type of

cancer affected him. The government kept a tight seal on details of the

president's treatment and declining health.

The death of the Venezuelan

president leaves a sharply polarized country, with no clear successor for his

party and an untested opposition. Chavez' passing means new elections will be

held, although he had said previously he wanted Maduro to succeed him.

Chavez was born in the plains

state of Barinas, in southwest Venezuela, on July 28, 1954, the third of the

seven children of two educators.

As a child, he was an altar boy

who went on to develop a great love of baseball. Recently, even as questions

arose about his health, the media-savvy Chavez sought to reassure the public by

playing catch with his foreign minister on state television.

Chavez became more

authoritarian over the years

As a young man, he enrolled in

the Military Academy of Venezuela, reaching the rank of sub-lieutenant in 1975.

He joined the parachute corps of the army and rose through the ranks to become a

lieutenant colonel.

His first political steps came

when he founded the Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement, or MBR-200, in 1982. A

decade later, on February 4, 1992, he led a failed military rebellion against

then-President Carlos Andres Perez. He also made his first public appearance in

front of the television cameras.

"Compatriots, sadly for now the

objectives that we proposed were not achieved in the capital city," he said.

"That is to say, we here in Caracas did not succeed in gaining power. You did it

very well out there, but now is time to avoid more bloodshed. Now is time to

reflect and new situations will come."

Chavez served two years in

prison before then-President Rafael Caldera granted him amnesty.

Chavez went on to form a new

political party, the Fifth Republic Movement, which carried him to a

presidential election victory in 1998. His fiery campaign speeches blamed the

traditional parties for corruption and poverty.

Chavez married twice and

divorced twice. He had three children with his first wife, Nancy Colmenarez:

Rosa Virginia, Maria Gabriela and Hugo Rafael.

Years later, he married

Marisabel Rodriguez, with whom he had a fourth daughter, Rosa Ines. He divorced

in 2003; Venezuela has had no first lady since then.

Upon taking office, Chavez made

rewriting the constitution one of his first orders of business. A July 2000

referendum affirmed the new constitution, which the government printed as a

little blue book that Chavez used regularly as a prop during speeches.

In the following years, the

charismatic Chavez rattled off a string of electoral victories that made him

seem almost invincible.

He won re-election in 2000,

survived a recall election in 2004, and won another six-year term in 2006.

Chavez secured another

re-election victory in October, describing his win as "a perfect battle, and

totally democratic." He vowed to "be a better president every day."

A turning point for Chavez came

in April 2002, when a coup briefly removed him from office.

But the interim government

couldn't consolidate power, and within 48 hours, with the help of the military,

Chavez returned to power.

While short-lived, the coup had

a profound effect on Chavez, who took a more accelerated authoritarian and

leftist turn afterward.

Human Rights Watch wrote in 2010

that the coup provided a pretext for policies that undercut human rights.

"Discrimination on political

grounds has been a defining feature of the Chavez presidency," the report

concluded.

"At times, the president himself

has openly endorsed acts of discrimination. More generally, he has encouraged

his subordinates to engage in discrimination by routinely denouncing his critics

as anti-democratic conspirators and coup-mongers -- regardless of whether or not

they had any connection to the 2002 coup," the report said.

He clamped down on

broadcasters, other media

Consolidation of power in the

presidency -- to the detriment of separation of powers -- became a theme in

Chavez's policies.

Another challenge to Chavez's

rule followed the coup. From December 2002 to February 2003, a crippling general

strike pressured the president. The economy took a hit, but Chavez outlasted the

strikers.

The following year, in 2004, the

opposition gathered enough signatures to hold a recall referendum on Chavez, but

again, the president survived.

Chavez's vitriol toward the

United States also increased in the period after the brief coup because

Washington had tacitly approved it.

In one of his most memorable

insults, Chavez said of Bush in 2006 before the U.N. General Assembly:

"The devil came here yesterday.

And it smells of sulfur still today."

In 2007, Chavez tasted defeat

for the first time, in a referendum seeking approval for constitutional reforms

that would have deepened his socialist policies. Nonetheless, thanks to a

National Assembly friendly to him, Chavez achieved some of his goals, including

indefinite re-election.

That same year, Chavez created a

new political party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, which merged his

party with several other leftist parties.

His detractors accused him of

being authoritarian, populist and even dictatorial for having pushed through a

constitutional reform that allowed indefinite re-election.

Increasingly, Chavez used

legislation to clamp down on broadcasters and other media. His government

relentlessly went after opposition broadcaster Globovision, accusing it of a

number of violations, from failure to pay taxes to disregarding a media

responsibility law.

The broadcaster is the last

remaining TV network that carries an anti-Chavez line, since the president

refused to renew the license of another opposition station, RCTV, allegedly over

telecommunication regulation violations. The station had to go off public

airwaves and transmit solely on cable.

Abroad, Chavez was also known

for his colorful -- if sometimes strange -- statements.

Last year, after several Latin

American leaders were diagnosed with cancer, himself included, he wondered if

the United States was behind it.

"Would it be strange if (the

United States) had developed a technology to induce cancer, and for no one to

know it?" he asked.

During a water shortage that

Venezuela suffered in 2009, he took to the airwaves to encourage Venezuelans to

take showers that lasted only three minutes.

At a summit in 2007, his

repeated attempts to interrupt resulted in King Juan Carlos of Spain saying to

him, "Why don't you shut up?"

Chavez was a believer that the

days of the "Washington consensus," a model of economic reforms favored by the

United States for developing countries, were over.

Along with Cuba, Ecuador,

Bolivia, Nicaragua and some Caribbean countries, Chavez formed the Bolivarian

Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, or ALBA, a group intended to offer an

alternative to U.S. influence in the region.

As president, Chavez made clear

his ambitions of being a regional and international leader who left, in his own

way, changes that awakened passions and feelings in favor and against --

everything except indifference.

CNN's Mariano Castillo reported from Atlanta and

journalist Osmary Hernandez reported from Caracas. CNN's Catherine E. Shoichet

contributed to this report

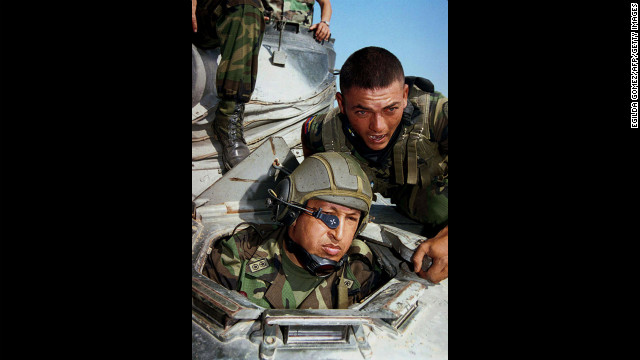

Venezuelan president-elect Chavez visits Bogota, Colombia,

on December 18, 1998. On December 6, Chavez had been elected the youngest

president in Venezuela history.

Venezuelan president-elect Chavez visits Bogota, Colombia,

on December 18, 1998. On December 6, Chavez had been elected the youngest

president in Venezuela history. President

Chavez greets supporters with his then-wife, Marisabel Rodriguez de Chavez,

beside him as he arrives to preside over a parade in his honor on February 4,

1999, in Caracas. Chavez was sworn in as president on February 2

President

Chavez greets supporters with his then-wife, Marisabel Rodriguez de Chavez,

beside him as he arrives to preside over a parade in his honor on February 4,

1999, in Caracas. Chavez was sworn in as president on February 2 Chavez

inspects military maneuvers of the national Air Force on March 17, 2001, in

Catilletes near the border with Colombia. In June 2000, Chavez was re-elected to

the presidency for a six-year term, under the new constitution created by his

government in 19HIGHLIGHTS

Chavez

inspects military maneuvers of the national Air Force on March 17, 2001, in

Catilletes near the border with Colombia. In June 2000, Chavez was re-elected to

the presidency for a six-year term, under the new constitution created by his

government in 19HIGHLIGHTS

No comments:

Post a Comment